Timelines in the Primary Classroom

Timelines are an essential part of the History curriculum - every unit of History learning will most likely include timeline work. But why do we actually need to teach timelines and how can they be used effectively to develop pupils’ understanding of historical concepts?

We’ve all probably seen - or even taught - lessons like this: pupils are given cards and asked to order them from earliest to latest on a timeline. Although this may be valuable with some of the youngest pupils in school, this is just sequencing. Misconceptions pupils may have are that events are evenly spaced and follow each other consecutively.

But History is not that straightforward! History is messy! Pupils need to understand the scale of timelines and the deeply complex relationship between periods of history and events. This is what the National Curriculum says:

know and understand the history of these islands as a coherent, chronological narrative, from the earliest times to the present day: how people’s lives have shaped this nation and how Britain has influenced and been influenced by the wider world

understand historical concepts such as continuity and change, cause and consequence, similarity, difference and significance, and use them to make connections, draw contrasts, analyse trends, frame historically-valid questions and create their own structured accounts, including written narratives and analyses

So how can timelines aid this?

The first aspect of timelines I’d like to talk about is scaling. It’s really important pupils understand the scale of time and the intervals between periods and events. They should be measured accurately so children can see exactly how much time elapsed between certain events and make connections.

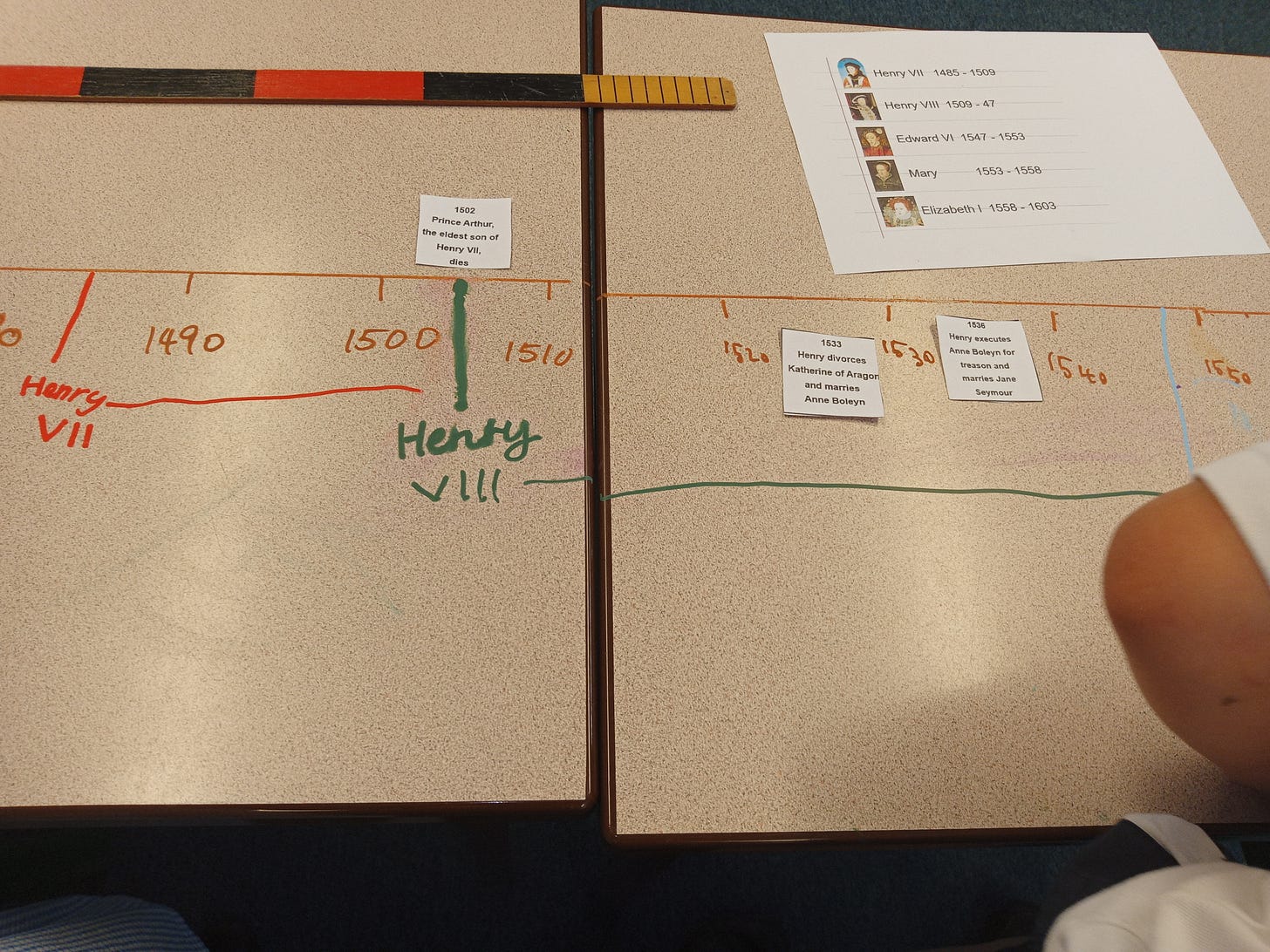

In my classroom, I’ve done this by getting pupils to apply their Maths skills measuring out a timeline on a large scale. Using meter sticks and chalk markers, they drew a timeline of the Tudor period on the tables (we discussed the concept of decades and centuries and most decided 10cm would be a good scale for a decade). They then marked out the reigns of each Tudor monarch on a timeline from 1460 - 1610.

This meant that they understood that the reigns of each king or queen lasted for a duration of time and weren’t just a one-off events, which might have been a misconception had I - for instance - given them cards to place along the timeline. They were also able to visualise really clearly who reigned for the longest or shortest amount of time. They also loved the fact they were allowed to write on the tables.

After this, I did give pupils cards with some key events from the Tudor period, which they had to place on their timelines using their measuring and estimating skills (some more able pupils worked out they could measure 1cm per year and therefore really accurately scale events).

This activity could also be done on a larger scale - if you wanted to work out where a particular time period fitted in you could scale you timeline in centuries and show where a period would fit in alongside other periods studied (for instance, 1m could become 1000 years).

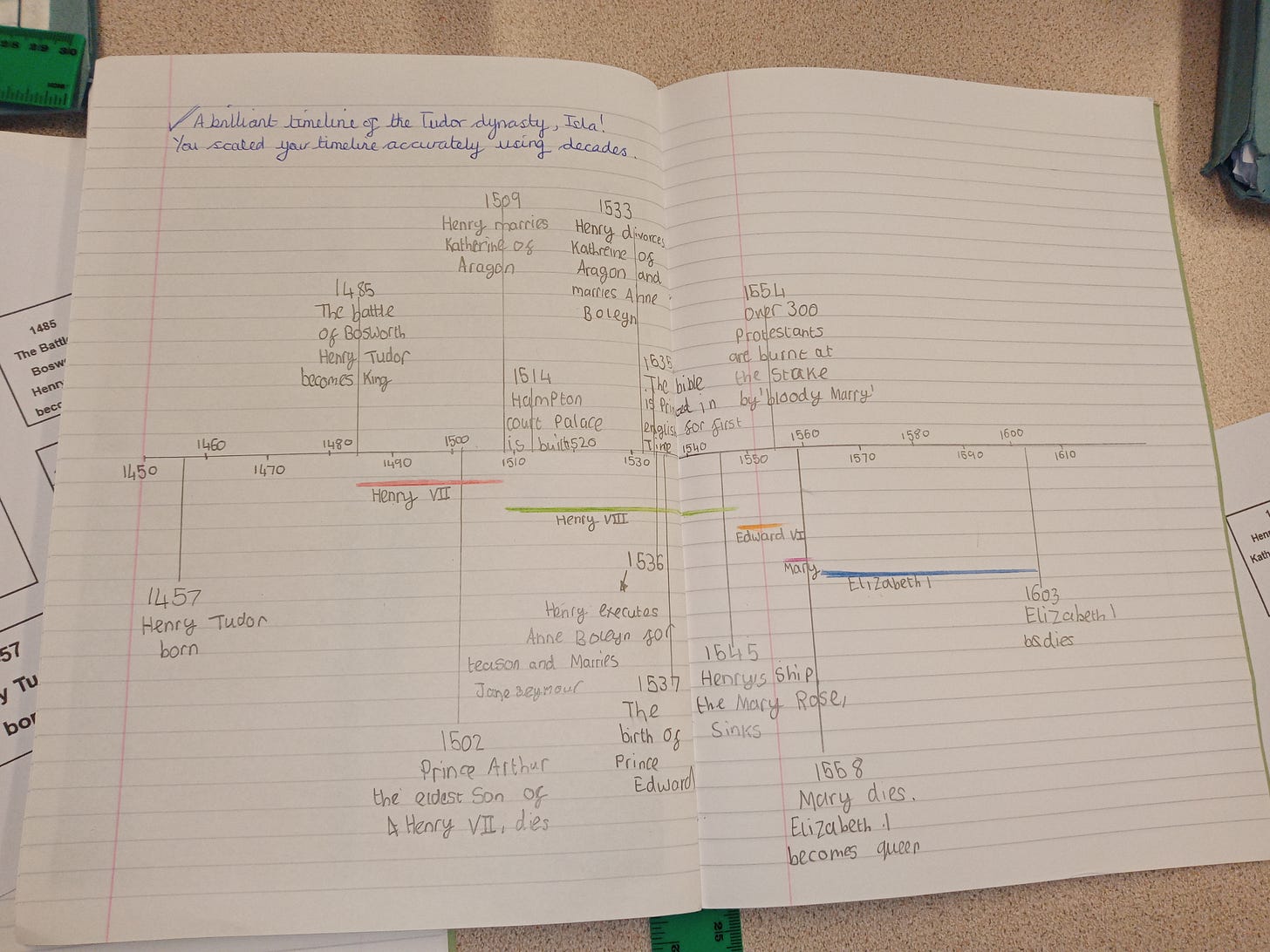

In the following lesson, pupils were able to replicate what they had done on paper; a task which I think they would have found more difficult without doing the interactive task first. I also asked them to work out, using subtraction, how long the Tudor period lasted, how long each monarch’s reign lasted, how long before us the Tudor period was and also what was the interval between the Tudors and the end of the Roman Anglo-Saxon and Viking periods. They then wrote some information in their books about this.

We discussed chronological concepts such as duration and intervals of time between periods and how we could find this out. This is very much a work in progress for me, but my next step is to develop how pupils think about chronology across school and pupils’ confidence in talking about chronology: chronology isn’t just making a timeline - it’s how you use it afterwards and the links you make. Chronological understanding can also be shown through a short written piece of work as shown above (again this is an aspect I am hoping to develop in my role as History leader).

Pupils also noticed a trend after making their tabletop timeline: they noticed that lots of events happened during the 1530s and 40s - bu why? They had lots of questions about why this section was so busy. We’re going to return to this and discuss why in later sessions about Henry VIII’s reign and discuss the Reformation in more detail.

As our unit on Tudor monarchy progresses, I intend to ask pupils to add more key events to it as they discover more. Timelines can be added to throughout units (and even academic years); they shouldn’t just be done and dusted in one lesson to tick a box on chronology but should be an ongoing process that adds to pupils’ understanding of the complex web of interconnected events that is History.